International – Why Team Scotland and Not Team GB

Have you ever wondered why Scotland has a separate team in the Commonwealth Games but not the Olympic Games?

In many ways we do not consider this unusual.

Scotland has national representative teams in most sports. The national football and rugby teams have prolific histories and enormous national support.

But in sports such as athletics, cycling, swimming and gymnastics, which all feature in both the Commonwealth Games and Olympic Games, we more often than not associate national representation with Great Britain rather than Scotland.

Although nationalist sentiment, identity and values play a large part in any national representational sport, the historical reasons for the Scotland/GB divide are often more politically and administratively driven.

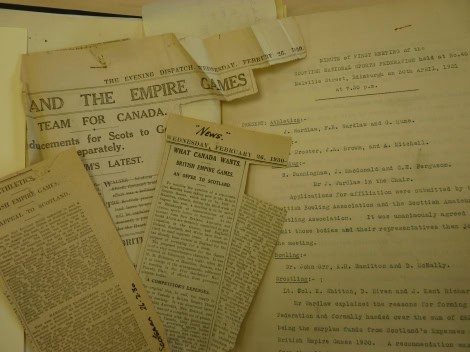

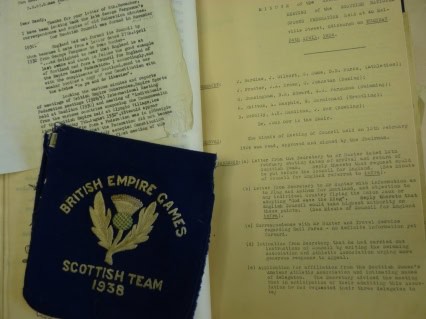

The clues as to why Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England have separate identities during Commonwealth sport can be found in the early minutes and letters from the archives of Commonwealth Games Scotland (CGS), the organisation that has run the Scottish team since the 1930s.

CGS represents the governing bodies of Commonwealth Games sports in Scotland and manages Team Scotland. CGS is also one of seventy-one members of the Commonwealth Games Federation, the international parent body for the Games.

The CGS Archive at the University of Stirling encompasses approximately one hundred and fifteen linear metres of records, collected over the full period of the 84 year history of the Games, with thousands of letters, memoranda, minutes, publications, artefacts, film and press clippings documenting the activities of the Commonwealth Games movement, its philosophy, organisation and mission. It is one of the most substantive archives of sports administration in Scotland and unique as a record of the nation’s representation in multi-sports events.

In order to answer the question ‘why Team Scotland?’ we first need to understand the motivation for what was originally called the British Empire Games which had English roots but was ultimately driven forward by a Canadian.

Origin of the British Empire Games: Canada Takes the Lead

The Canadian sports historian Bruce Kidd notes that the 1920s and 30s saw a growing athletic ambition among many Canadian sports administrators. Canada had joined the League of Nations in 1919, and they began to become ‘a nation of influence through sports’, which included pushing through the idea for a separate Winter Olympiad, introducing the idea of ‘demonstration’ sports in the Olympics, and driving the formation of the British Empire Games.

As Kidd notes:

They sought an independent Canada, too, but within a federation of countries from the British Empire. They had always regarded sporting competition with Britain and the other dominions as on a plane above other international competition. p.71.

The idea for conceiving an Empire Games is credited to Sir Astley Cooper who proposed the concept of a pan-Empire sports festival to The Times in 1891. Unfortunately for Cooper, his idea was superseded by the modern Olympic Games introduced by Pierre de Coubertin in 1896, which effectively ended his hopes for a international sports tournament. The 1911 Festival of Empire and inter-Allied competitions of the war were close approximations of Cooper’s original idea, but it was not until the late 1920’s that the concept of an Empire Games resurfaced from within Canada.

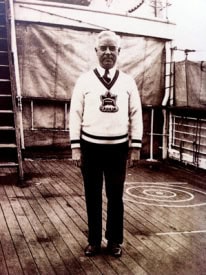

M.M. ‘Bobby’ Robinson (pictured left) was a journalist and member of the Canadian Olympic Committee and had overseen the Canadian team for the 1928 Olympic Games in Amsterdam. He raised the idea of a Games every four years in between the Olympic Games to his counterparts from Britain, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, with the idea of hosting the first Games in Hamilton.

Again, as Kidd writes:

Robinson had obtained the city’s promise to build new facilities, pay for visiting athletes’ and officials’ meals and accommodation, and assume any overall loss in the operations; as well, Hamiltonians had already begun to pay two dollars each to become ‘boosters’ of the Games. p.71

Australian, New Zealand and South African representatives agreed to confer with their respective federations, but the British were less convinced of the idea. The British Olympic Association were concerned an Empire Games would undermine fund-raising efforts to send a team to the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Games.

As Robinson later wrote: “the support from the leaders of the Old Country was but lukewarm – the result of a thought that an effort was being made to supersede Olympic competitions with a purely Empire show.”

Robinson made plans to travel to London with the aim of reassuring the BOA and associate members that their concerns were unfounded. He took with him the promise of $30,000 in travel grants from the people of Hamilton, an early example of hosts lobbying for support through financial incentives.

There was a public outpouring of imperialist sentiment from various Canadian advocates, all of whom supported the initiative. Behind it all was talk of uniting the ‘red-coloured lands’ of the Empire:

“Today the British Empire is held together by sentiment rather than force, and whatever develops friendships will stimulate that understanding and goodwill. Therefore, an assemblage of the best athletes in the Empire will not only strengthen national pride, but should develop social ties that will tend to seal more strongly the bonds of Empire.”

Henry Roxborough, cited in Kidd, p.72

The Celtic Nations Unite in Disunity

Although Robinson was persuasive, the BOC remained steadfast in their opposition to an event rivalling the Olympics.

A newspaper clipping in the CGS Archive from The Evening Dispatch, (Wednesday, February 26, 1930) carries the headline: “A Team For Canada: Inducements for Scots to Go Separately”.

The article reports on a meeting of various Scottish sporting bodies on 25th February 1930 in Edinburgh to consider the prospect of joining the Empire Games being set up in Canada.

It reported that, “the Canadians want a separate Scottish team, and are prepared to help financially if one can be got together”.

A further article on the same page continues “British Empire Games. Will Scotland Send a Team to Canada? Financial Help.” It reports on a meeting to decide if it was practical to send a team to the first Empire Games in Hamilton, Ontario in August 1930.

Bobby Robinson as the instigator of the Games addressed members of the Scottish sports federations in the Free Gardeners Hall, Picardy Place, Edinburgh.

James Warlaw, president of the Scottish Amateur Athletics Association presided over the meeting, where the initial idea for the Games to be exclusively based on track and field events was overturned following pressure from representatives of boxing, wrestling, rowing, swimming, lawn bowls, tennis, yachting and football for inclusion of their sports.

They had estimated the cost for sending each competitor from Scotland would be £60 per athlete. The article states: “The United Kingdom is now in the show with both feet. When the national committee was formed in London, the idea was to have a British team. They (the Canadians) had rather surprised them by saying that it was Canada’s desire to have teams from England, Scotland, Ireland, and possibly Wales.”

The Canadian move to ‘divide and conquer’ had won the day, and smoothed by the generous offer to the Scots of £200 towards the cost of sending its athletes.

Hamilton would put up the cost of the Games, including housing and subsistence for all the athletes. The journey would take one week to get there, one week for the Games and a week to return. It was resolved that Scotland would do its best to send a team and that the Scottish federations would meet in the City Chambers to decide how to proceed. The star athlete of the era was Eric Liddell, and it was hoped he might compete for Scotland.

Another newspaper article from The Scotsman reports similar information, but also additionally notes that Lord Derby was the president of the new Federation set up in London, but the Canadians debunked a British team and requested separate teams for the home nations.

The first Games were viewed as a great success. Hamilton got a new pool and $9000 of equipment. The revenue of $15000 helped repay some of the $19000 city grant. A Games Federation was established, and Johannesburg chosen for the next Games. The South African’s promptly made it clear that black athletes would not be welcome. In 1931, Canadian’s and others refused to accept the exclusion and forced the Federation to change venue to London.

It was not until after the first British Empire Games, on 30th April 1931, that the new Scottish National Sports Federation (now Commonwealth Games Scotland) was formed. It’s first Secretary, George Ferguson, took delight in the knowledge that Scotland had formalised its association with the Empire Games ahead of his English counterparts. In a letter to Evan Hunter of the English federation in April 1932, Ferguson writes:

“I am delighted to hear that England is at last awake and about to follow the good example of Scotland and form a Council for England of the Empire Games Federation. I accordingly, and with the compliments of Scotland, send to our weaker brother a copy of our Constitution with the advice “Go ye and do likewise”.

A fantastic bit of bravura from the Scot to the English administrators of sport. The letter notes a general agreement to form a Federation as early as 1928, and certainly by 1930, but that a constitutional arrangement was not in place until 1932 when they met at the Los Angeles Olympic Games. The first ever meeting of the Council of the British Federation took place in London in January 1933.

So the answer to the question, ‘why Team Scotland?’, is that the British Olympic movement, which was dominated by the English, was usurped by the Canadian journalist and sports administrator Bobby Robinson in his attempts to rally support for the Empire Games in Hamilton by directly engaging the Scots, Welsh and Irish to establish their own teams and circumvent any attempts of blocking the Games by the English.

Professor Richard Haynes

Reference:

Bruce Kidd (1996) The Struggle for Canadian Sport. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.